no person, trying to take responsibility for her or his identity, should have to be so alone. There must be those among whom we can sit down and weep, and still be counted as warriors.

Adrienne Rich

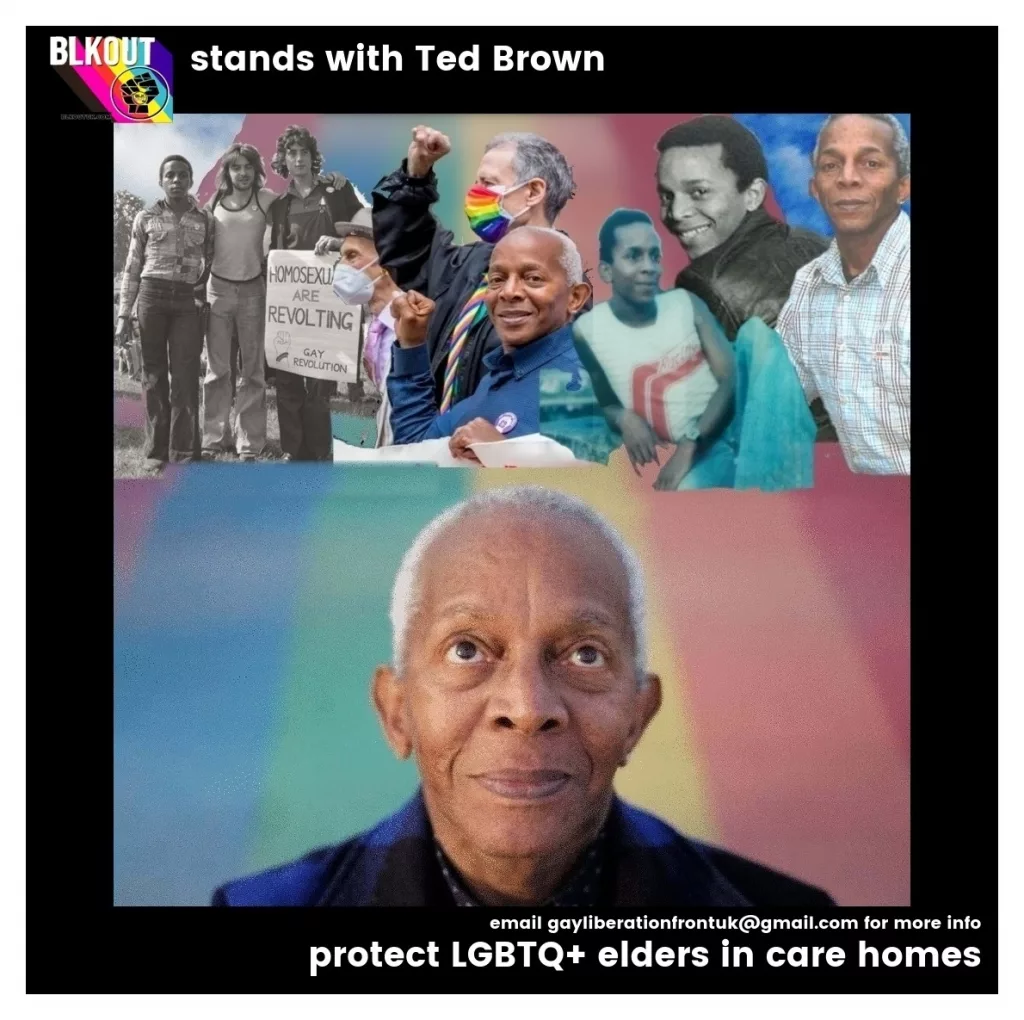

50 years ago, a group of outcasts gathered in London’s Hyde Park to picnic and play party games. They were on a high from having just completed London’s first ‘Gay Pride’ March. They had been inspired by the movement that had coalesced around demands for an end to police brutality, after years of raids on the Stonewall Inn, New York, just three years earlier. Though the more significant influence on their thinking seems to be the West Coast ‘hippy’ radicalism of Berkeley, Oakland and San Francisco. Between 500 and 2000 people are estimated to have taken part in some aspect of the day of protest, organised by the committee of under-21s of the Gay Liberation Front. The decriminalisation of homosexuality, ‘won’ five years earlier, had not applied to adults under 21; the GLF believed in those most impacted taking the lead. A young Ted Brown, an early and an enthusiastic member of the GLF was tasked with organising the Trafalgar Square ‘kiss-in’ that preceded the march to the Hyde Park party.

The GLF London, was less than two years on from its first meeting at the London School of Economics. It would disband a year later – shining brightly but briefly. Perhaps this was inevitable, for a group seeking to resist (re)creating oppressive hierarchies. They had begun the process of movement-building, articulating demands, agitating for change, drawing directly from the organising playbook of radical Black liberation. Bob Mellor and Aubrey Walter, the GLF’s founders, had met at the Revolutionary Peoples Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia. The event, convened by the Black Panther Party, heard Huey Newton, advocate in person for his strategy of building common cause with movements for women’s and gay liberation. In doing so, he directly challenged homophobia and violence, locating the problem with heterosexual men’s ‘insecurities’.

In his teen years, Ted Brown, moved from Harlem, via Jamaica, to Brixton, where he still lives today. He helped to organise London’s first Pride March on July 1st, 1972. One of few Black people present, Brown described the day as ‘amazing’, in a recent interview for The Guardian. Remarkably, he is making plans to attend an anniversary march being organised by a revived GLF, 50 years after the first. He will be marching not to take a wistful trip down memory lane, but to launch a new campaign in response to harrowing, homophobic elder abuse suffered by his partner in a care home during the twilight of his life.

Brown’s campaign is demanding assurances from regulators, and accountability on dignity in care for LGBT elders from care home proprietors.

Not yet born when Ted Brown orchestrated the kiss-in around Nelson’s column, I am full of admiration for him, and the efforts of so many of his generation who had to fight to live their lives, fight to love. Their bravery is even more remarkable because they fought without the luxury of knowing how it would all work out; without guarantee of eventual vindication. We must not forget how transgressive an act a ‘kiss-in’ was – it took another 17 years until mainstream TV aired a same sex kiss between men. Piers Morgan, reporting in The Sun in January 1989, described that kiss as a ‘homosexual love scene between yuppie poofs’, adding a disingenuous concern for child welfare, ‘when millions of children were watching’. The ‘culture wars’ we currently experience rely on dog-whistles and coded epithets; LGBTQ Britons were not afforded even this fake politeness. The connection between hate speech and hate crime is well documented.

A movement for queer liberation, intertwined in moral purpose and method with radical Black political organising in the US, in which Black people were not only present, but prominent, was largely met with suspicion by campaigners for racial justice in the UK. Active resistance towards solidarity, or benign neglect of allyship, or denialism of Black queer existence became the approach. The repercussions of the trauma caused goes largely unrecognised. The waste of talent and potential driven by suspicion of those identifying as both Black and queer, and the missteps that could have been avoided by choosing the side of the oppressed over the oppressor echo and reverberates across movements for racial justice, even today.

I ran my first racial equality focused charity in 1994 at the age of 20. I left the racial justice think-tank, Runnymede Trust, when I was 40, after a 5-year stint as its first Black director. 1994 was also the year in which I ‘came out’ as a gay man. I experienced my first Pride the following year, while volunteering as a ‘parade’ steward. I now work with bi, gay and/or trans men of African descent in the UK, to develop BLKOUTUK – an organisation ‘to save our lives’.

There is a particularly English flavour to the lack of leadership, uncomfortable silences, and ‘polite’ avoidances that have typified a half century of non-responses to the needs of Black and brown queer Britons. Throughout the 90s and 00s there was next to zero intervention from racial justice organisations on behalf of queer people of colour. Section 28? – nothing. Equalising age of consent? – ambivalence. The army, same-sex couple adoption? The silence was deafening. The debate was left to the religiously dogmatic to argue with queer Black and Asian folk. Way to ally. This failure still needs to be addressed and atoned for among racial justice advocates here. The claims of a greater proximity to religious beliefs/practice as the fig leaf behind which to shelter, ring particularly hollow in hindsight. The visibility and challenge posed by queer leadership of Black Lives Matter in the US, posthumous awards given by President Obama to Bayard Rustin, or the rediscovery and re-presentation of James Baldwin’s writing, cannot be claimed as evidence of meaningful change in UK-based movements for racial justice by a mystical diasporan association. The blank looks I get today when I ask Black youth employment organisations, adolescent mental health interventions, or minority ethnic financial inclusion courses about the patterns of discrimination that impact on the Black queer people they work with, are testament to how far we have allowed heterosexual ‘insecurities’ about sexual identity to lead to worse services for Black queer people.

There needs to be a reckoning with those parts of British movements for racial justice yet to acknowledge those times where the violence and harm wielded by our oppressors came to be understood as the lingua franca of struggle – as if liberation for some could ever truly be won at the expense of the further subjugation of others. Stand back if you are ‘too Black’, ‘too unconventional’, ‘too controversial’, ‘too queer’, your liberation can wait. Those thrown under the bus in the quest for the weak sauce of temporary tolerance are numerous – in exchange for this week’s favourable news coverage in a paper that will happily trash your work next week, or to look fashionable by siding with the teenage reggae artist (just because it’s a hot riddim that he demands your brother’s violent execution to). Ultimately, they would discover, in a lesson learned much too slowly, and at vast expense, it is only truth that sets you free.

Movements for racial justice seemed to forget who they were there for, seeking respectability before justice. Using strictly ‘government names’, and employing their best ‘phone voices’, it is unsurprising that the distance between the experiences of Black and brown people and the organisations that claimed to represent them grew. A network of local race equality councils, youth movements and elders’ social clubs withered over these decades, as increasing numbers of people failed to recognise who they stood for. Offered opportunities to build common cause, for example via the Stop Murder Music Campaign, or at the untimely and tragic death of Justin Fashanu, racial justice leaders remained missing in action, or worse chose to side with the oppressors. The impact was that Black and brown people were increasingly viewed as ‘socially conservative’ while literature, the fine arts, pop music, children’s television, PM David Cameron’s opportunistic, ideology-lite, ‘Chipping Snorton’ set, and even the English Defence League, vocalised support of queer rights, before many Black leaders seemed to get the memo.

Too often missing in action in addressing sexism and homophobia, movements for racial justice lost out on the insights of Black queer people. We are currently victims of a ‘Jedi mind-trick’ (just not the one Labour leader Kier Starmer has identified), where in the wake of the latest series of Black ‘lynchings’ in the US during a global pandemic, the establishment talked up the prospect of a ‘racial reckoning’, and then, almost imperceptibly, shifted to discussing that same ‘reckoning’ in the past tense, as if it happened and we missed it. All reasonable requests for accountability are subsequently met with a roll of the eyes or an exasperated sigh. ‘You’re obsessed! Not again, hadn’t we dealt with this already?’ they remark, usurping the position of victim, and asking for mercy. Calling out racism ‘again’, is regarded as the action of a ‘bad sport’, or worse a self-serving liar whose demands ought to be disregarded.

One of the ‘joys’ of life at the intersections of homophobia/patriarchy and anti-Black racism is that both social forces generate similar avoidance tactics from those who believe they stand to gain from doing nothing to dismantle them. It is like having a mediocre poker player as opponent, the more hands you play, the more likely you are to spot their ‘tell’ – repetition makes recurring patterns far easier to spot. In unguarded moments, I’ve heard anti-racist leaders who should know better talk of a ‘Gay Agenda’, or reassure me that some of their best friends are homosexual, or declare envy at the progress of queer rights, in comparison to racial justice, as if there is only so much justice to go round, and a different oppressed group has taken progress that they were somehow entitled to – excusing the powerful from scrutiny. I’m wise to it now – and not just the actions of racial justice focused organisations; there is a parallel critique for LGBTQ organisations who see Black people solely as a threat; willing to use Black queer people as a tool with which to feed their racist ‘saviour complex’, exempting Black queer folk, who they award a deracinated ‘pass’ and a portion of liberal pity, that they never asked for.

At a recent overseas conference, among a highly impressive gathering of Black mental health advocates and innovators I found myself in floods of tears answering a question that I’d addressed numerous times in the past without the water works. On my mind were all my Black queer contemporaries who had only been served with excuses when action was necessary. Who, told that their liberation had to wait, decided that they couldn’t wait. In some throats were the standard accusations of queer deviance and disloyalty to the cause of racial justice. What made my tears flow, however, were a series of words I had heard too rarely. Words of unequivocal solidarity, of community, of determination to build our movements from actions and relationships that will be part of our new world, rather than those that replicate the violence of the old. Lockdown, my tears reminded me, had taken a lot out of me. Through those involuntary tears, however, I felt held by a community for the first time in a very long time.

I am increasingly proud of the next generation of activists here in the UK who have grown up with the shorthand of memes and hashtags that so elegantly call out lazy thinking and are less forgiving of rank hypocrisy. Similarly, I’ve encountered some amazing minds from activists across the diaspora, who are building utopian queer communities, often in social contexts and regimes that threaten their lives. For too many Black queer people globally, a public kiss-in today would mean more than clutched pearls, or a series of strongly worded letters to the Telegraph. Despite 50 years of visible activity and inspiring campaigning here in a favourable social climate, we are yet to experience what the full inclusion of queer voices in Black and brown communities in the UK could deliver for the benefit of all. While it is great to see some of the work undertaken in the 80s and 90s being documented, we cannot yet forget or forgive those who failed to lead, and there must be a collective commitment to repair the damage done, and to learn from those mistakes, lest we repeat them.

Our aim, through BLKOUTUK, is to support the creation of digital and IRL spaces where Black queer people will be able to build those networks in which they will be able, in Adrienne Rich’s words, to

“sit down and weep, and still be counted as warriors”

Leave a Reply