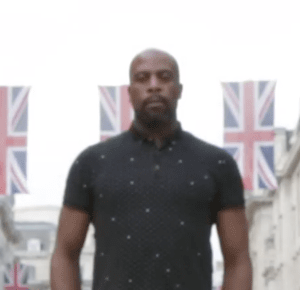

How many of us today wish we had Boyega money?

Those of us who grew up without the privileges of monetary wealth, know the crashing disappointment of being told that that which we most desire is not for the likes of us.

Mums would remind us that,

‘We don’t have *McDonald’s/Scalextric/ski trip/Nike trainers/theatre money.‘

*DELETE AS APPROPRIATE

Life towards our end of the class structure, behind the barriers erected by racism, meant that our migrant parents worked in jobs they endured on the basis that we, their offspring, wouldn’t have to do the same in the future. What were everyday niceties to some, remained luxuries to us, and were largely off the menu. We understood; got used to not asking and (mostly) learned to cherish what we had. We locked the want away until the day we could afford to want.

‘One day’, we said to ourselves, ‘One day’.

In the playground, classroom, shop, and workplace; on the sports field, bus, train, and dancefloor, I have similarly locked away the desire to tell racists all about themselves. I postponed my ire. I waited for that time in the future when I could even consider fulfilling the desire to ‘do-a-Boyega’, to tell them to ‘just f**k off’. Often, I’ve made the judgement that I couldn’t afford to even want to do what I wanted.

Instead I found ways to call out racism ‘politely’. I tried to reason with the de-humaniser and empathised with their plight – they did not know what they were saying, how could they? They were under pressure? They were too old to get that things have changed, or too young to know the damage that they were reinforcing. Their racism euphemised as bias; their bias described as unconscious rather than unconscionable.

I joined in making perfectly good words meaningless, bending definitions so out of shape so that irrational fears could be addressed in rational debate – xenophobia, Islamophobia, and homophobia were discussed rather than dismissed, allowed to look justified through equivalence, and those who harboured hatred were given succour.

Subsequently, I joined in appearing surprised when rational choices were not made by the irrational. Irrationality infected our public debate. Leading it to become so debased that 9ft high lies on the side of buses were still not big enough to disqualify a candidate from election to the highest office.

I did not dare to want what I could not afford. My patience was interpreted as virtuous. I could wait. Unlike so many of those around me who gave up what they believed about our future, simply out of boredom with the argument.

To my shame, I chided other Black people for being too outspoken, for speaking rashly, or being too radical. I became annoyed at them for making demands that displayed a lack of trust in the slowly-slowly strategy of the powerful, for giving into urgency for justice. Meanwhile those who challenged racism head-on; demanding justice or calling out ‘divide and rule tactics‘, were hauled over the coals in the media, side-lined, passed over for promotion, and made marginal. I interpreted this a s a warning and hid my wants still further away. By contrast, those who could persuade the aggressor to pause, feign contrition, congratulate themselves for neutralising a PR crisis, and then continue on as if nothing had happened, were lauded as highly prized; and then quickly discarded. Showing their hand and achieving nothing of substance.

Flashpoints came and went. Teachable moments passed without lessons learned. The racist murder of a teenager led to a series of inquiries that would have led neutral observers to believe that our society needed a definition of ‘institutional racism’ more than it needed access to justice for all. Independent commissions met and opined. Laws were amended and refined, HR experts held conferences, and governments sought to triangulate, giving with one hand – so that a racist act could be designated as such by its victims – while taking with the other, because of course no one is racist, making any accusation of racism mean-spirited, and any racist the victim of a witch-hunt.

All the while, we knew that locking our wants away was changing us, making us second guess every statement or act in case our truth slipped out and ruined us. Constant fear of racism began to have more impact on us than the racist acts themselves as we tensed, waiting for the fatal blow. All the time being told that it would never happen again. Until it did. And it did.

Almost as a distraction tactic, we collected data in response to the non-response. Every public authority, and then even the PM’s office went in hard for data. In the hope that that one nugget of information, would be the Rosetta stone. We search for that one defining factoid that cannot be sent back for further verification – in hope that a killer fact could end the racism before the racism killed us.

If only they would see . . . but numbers beget more numbers and act as proxies that distract from what is important; our people. People who were children of the first wave of post war Caribbean migrants who had been at the vanguard of Black British cultures, symbolic, embodied connectors of Black communities in the UK to the Caribbean homelands, found themselves suddenly punished for that connection; arrested, and deported to places they had barely been, as if their lives (and by implication ours) here had been a temporary aberration. Instead of ‘a new hope’, a society better capable of taking its place in a new world order; exchanging the promise of the empire striking back, and a globally engaged colonisation in reverse instead of the limiting lack of ambition and narrow nostalgia of this island story.

In the whirl of the everyday, in the midst of an information revolution, we could see that coping with racism was driving us mad, destroying relationships, killing us.

Racism’s tentacles stretched so far and deep that they were now choking the want; until we were no longer sure that we even wanted to want. Ten years ago, young people who were asked about the end of racism retorted that that dream was better left to science fiction; that it was a waste of desire; a possibility only for their children’s children. Already, by the age of 14, they knew they did not have, and would never have, Boyega money.

It has taken COVID-19’s spread to put into stark relief the racial inequalities that we had become inured to.

A deadly virus has taken nearly 40 000 lives in Britain, and with them, removed the scales from our eyes. Now, we have all been witness to the ways that policies of neglect, quick-fixes, and denial kill Black and brown people in our state.

We have also seen how reliant our entire society is on Black and brown people as co-producers of the solutions to this crisis. Thousands took to the self-isolated streets to give them a standing ovation each week, while our parliament passed legislation to close routes for their entry, and extend the ‘hostile environment’ for migration. The first woman of colour to take leadership of the British immigration system stood at the socially distanced despatch box, appearing to take delight in declaring British minority ethnic communities as an inconvenience, a problem to be solved by reducing their number. Satirists must have torn up their notepads as truth overtook fiction.

In our locked down quarantine, we watched, stunned by the incompetence and dissimulation of our leaders and their courtiers. We have become resigned to the avoidance of truth among law enforcers, and the disingenuous whataboutery of our media. We now see how they contribute to our straitened lives and early deaths, rather than strive with us to create the society that we want.

We can no longer wait until we all have Boyega money – the kind of money that could free our tongues and unleash our anger, protected from consequence.

We have to invest in our shared future now and that may mean that ‘Karen‘ will have to cede her presupposed monopoly on sympathy and listen. That we, in turn will also have to cede some space for the young, the trans, the poor, the migrants, the disabled; for all of those we don’t hear enough from to be heard. Now is the time for real talk, real leadership, and action. Now is the time to answer what is it we really want?

Yet again, from our island standpoint, we view our Black American cousins take to the streets to demand justice; to assert that the Black lives of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor and Ahmad Arbery and Tony McDade matter. Minneapolis and Louisville neighbourhoods on fire as crowds shout, ‘No Justice, No Peace’, as they did in 2014 in Ferguson, after Mike Brown’s murder by the police.

If firearms were in more common usage by our own police we might be adding the name of Desmond Mombeyarara (tasered at a Manchester petrol station in front of his son for actions less egregious than those committed by the PM’s chief of staff) to this tragic litany. Our national police chiefs were forced to admit this week that they have disproportionately targeted Black people for stops during the lockdown.

Yet we continue to store up our wants for another day. When will we have enough credit to unleash our wants, to make our demands?

Is now the time to declare what you really want?

Right now, I have no interest in an inquiry into historical racial inequality and how we got here. No thanks to the appointment of another gaslighter-in-chief, to join the long line from the past half-century. Another patrician intervention in the tradition that has been handed from Rose to Rampton, to Scarman, to Macpherson, thank you but we already know.

I want a strategy so that we can assess progress, but given that government is only a part of the picture – their view too limited, their leadership compromised – I want a strategy that emerges from us, a community that is the solution, rather than a problem. I want a movement, rather than a collection of jobs for the favoured boys and girls.

I want to know how we shape a future that draws on all talents, where leaders lead for all rather than some, where we all have a stake in greater justice.

I want to know what we can all do from where we are to close the inequalities in education, employment, health, access to justice, housing, and political participation – because we all depend on being and doing better collectively. It is remarkable therefore how few of those who are expressing what our future might look like, look like me. Our civil society has not been immune to the kind of practices that have kept Black and brown people away from power, and in a position of supplicant.

We have been forced by the coronavirus to pause. A pause that comes after we’ve wasted a lot of time not tackling growing inequality and are reaping the results. In this time on lockdown what have we learned that we want to take forward, (apart from how to use a webcam)? In our communities we’ve seen the best of us and no doubt as time goes on we will hear about some of the worst. While news stories rush to cover the details of neighbourhoods coming together, the stories of those who are left out usually take longer to emerge. What is clear is that disruption to our society has happened. and in the great economic recession that follows, more disruption is likely. Thankfully, most of us will get through the pandemic. We can take neither ongoing unity nor increasing division for granted. The future will be what we make it.

Our next steps in this fertile moment for change, have to be rooted in honesty and filled with resolve for better. Many Black and minority ethnic people have been prevented from surviving this pandemic due to policies that kill. That so many could not see this imminent danger is a matter of basic health and safety that we need to bring to light and address.

We must enable each other to tell our truths – to define what we want and are willing to fight for, and discard the cluttered mindsets that get in our way or weigh us down. We need to build the coalitions that will keep our focus, refuse to leave any of us behind, and resist when systems seek to snap back to their old ways. And they will. ‘Power concedes nothing without demand‘ will be as true in post-pandemic 2021 as it was in 1857.

Thanks for the inspiration John Boyega.

We have known that ‘the time is always now’, but somehow been lulled into believing that justice can only occur in a parallel universe, or ‘in a galaxy far, far away’

We can no longer wait for that day in the future that never comes. It is no longer enough to say to ourseleves,

‘One day, one day‘.

We cannot be silenced by our fear that we might not be able to afford what we want, since the cost of going back to how it was, will ultimately leave us bankrupt. Can you afford to call racism out? Right now, can you afford not to?

Leave a Reply