The words of James Baldwin, my greatest literary hero constantly speak to me:

Something that irritates you and won’t let you go. That’s the anguish of it. Do this book, or die. You have to go through that. Talent is insignificant. I know a lot of talented ruins. Beyond talent lie all the usual words: discipline, love, luck, but most of all, endurance.

Since I was a child my educational and academic quest has been metaphorical armour worn to battle the storms of my life. And throughout these pursuits this armour has been the vehicle through which I articulated the Evidence of My Existence first as man; then as a Black man; and then as a Gay Black Man. Becoming an Associate Professor has taken me from Southside of Chicago to Brixton. And I know if not for the shelter of books and the protection of educational institutions, I certainly would not have survived this world, much less been able to cross the deep waters of the Atlantic. Nevertheless in recent months I made a momentous decision to leave academia with the aim to write a book.

During my time in the academy I struggled what my book long titled The Evidence of My Existence should be: an academic book; a novel; memoirs. I suspect my academic pursuits stifled the reconciliation of this struggle because academia requires and most values evidence based research. It values less the individual story. And perhaps because I love Baldwin so much; because his words speak so true to my life; I lack confidence in my ability to create a fictional story that embodies all I want to say. So before deciding to leave academia, I resolved to confine my exploration of self; to collect the evidence of my existence through written contributions to Blackout; apt as it was; conceived as a conversation for Black Gay Men by Black Gay Men.

But then the lovely Reggie Yates decided to go Chicago to examine the gun violence and poverty. And on a random Monday night I received nearly a dozen texts from friends encouraging me to watch it. I had already seen the program advertised and initially I chose not to watch it. I was mostly confident it would be good enough; generally accurate as one could expect from the BBC; done with compassion for those engaged; and mostly confident because I very much like Reggie. Nonetheless I didn’t think the documentary would tell me anything I did not already know about Chicago. Moreover I did not think I could handle seeing the documentation of gun violence poverty and other horrors beamed into my Brixton living room from my hometown; indeed the very community in which I was born and fled; and particularly so ahead of the Presidential election.

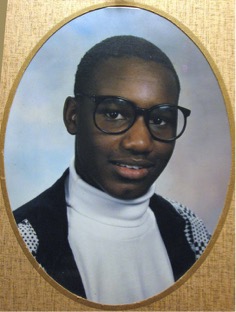

I was born on the Southside of Chicago in Englewood; the neighbourhood where Reggie filmed. My mother was most probably born there as well although this I do not know for certain. I do know that by age 18 after giving me the gift of life, she was forced to sell her body and she quite literally collapsed and died on those streets becoming one of America’s first casualties of the AIDS epidemic. And in the years that followed her death I lived in more foster homes than I care to remember before moving from Englewood to a group home when I was 9; the year I took the picture below.

Watching the program from the comfort of my sofa was very painful and more so because my man could not stop me from crying nor could he truly understand what caused my tears to flow. On that random Monday night and as those tears flowed I acknowledged what I have always known. I live with a huge sense of guilt for leaving Chicago and America; for being in London; and for choosing not to return. And in choosing initially not to watch Reggie tell me about ChiTown, I feared to view it would exacerbate that feeling; and it did! In my desire to confront this guilt, to face my demons I also call on the words of another literary great Maya Angelou who writes: “There is no greater agony than bearing an untold story inside you.” And despite this reaction and my many issues with Chicago and the country of my birth, it must be said; I love ChiTown. And to a lesser extent; I love America too! And again I am reminded of Baldwin’s words:

I love America more than any other country in this world, and, exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.

While I lack confidence in my writing I recognize that when I write to someone I love or write to someone about something I love, the words flow and I am unburdened by structure or form; motivated driven and fuelled to write by truth and passion. So with this awareness I’ve decided to write letters to individuals to speak to and to reflect on aspects of my identity that I needed to evidence and that being: my race, my sexuality, and my national identity. However I know and believe at the core of my being that these three parts cannot be compartmentalized. I believe true understanding comes at the intersection of all three, what I call the sweet spot; that space in understanding one’s identity where race, sexuality, and national individualities overlaps envelops saturates and informs who we are.

The first letter is to my foster brother Willie and through him to all the brothers of Englewood; and to all the brothers in Chicago’s other warzones. In my struggle to articulate my experience of race and how these experiences can only be understood through the lens of my sexuality and my national identity, I struggled to choose my words; academic or creative; big or small. And while I certainly wish for Black Gay Men to ‘GET IT’; it seems just as urgent (if not more) that I succeed in getting Willie to understand me/us as Black Gay Men; to know us in our truth and complexity. In writing to Willie, I want to speak to heterosexual Black men; to our community; and about the forms of masculinity that divide us. And I want him to know that despite the emotional physical and spiritual damage of his physical incarceration for more than half the 54 years he’s lived; his life has value; he is loved; and he is needed. And despite all that tells him otherwise, there is still hope yet for his life. But just as important I wish for him (and all the straight brothers) to recognize that we must begin to have an honest conversation that leads to a deeper understanding of one another and perhaps the realization of hope for our community. This conversation must be based on truth, and not myth, hypocritical religious judgement; or stereotype. The challenge is for Willie to hear the words of my letter. And in this I recognize that I must enable him to respond and perhaps through this exchange we will begin to know who we are. But I also recognize another challenge; we must articulate who we are without compromising the truth.

To be continued. . .

Leave a Reply